by Christopher Conlon

Anyone who remembers the 1970s remembers Truman Capote.

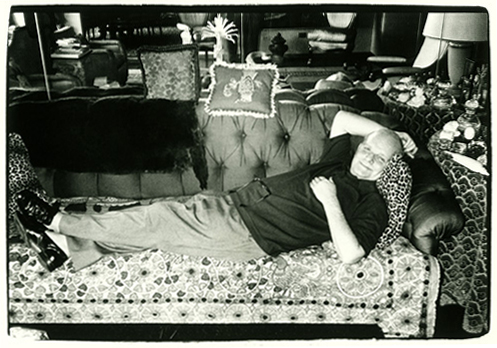

It would be impossible not to. Capote was then one of the most famous people in America, welcome on all the TV talk shows of the time, and only partly because of his finely-barbed wit. It was also his high-pitched voice and colorful style that made him—well—good television. In a time when the word gay was only just beginning to be accepted by the mainstream culture to mean “homosexual,” Capote was as gay as could be, and not trying to hide it. In fact, he celebrated it.

In that period, when I was young, every comedian could be relied upon to have a Truman Capote impersonation, as surely as they had a Richard Nixon or a Howard Cosell. Capote was that famous.

But famous for what?

I didn’t know, and neither did thousands and thousands of kids like me. Was he some sort of comedian? An actor? (Well, he was, actually, having played the villainous “Lionel Twain” in Neil Simon’s Murder by Death.) I was in college before I learned that Truman Capote was considered to be one of America’s greatest writers. It was even later when I began to understand that the Capote I’d first encountered on TV was, for all his garish flamboyance, only a pale shadow of what he’d once been. The 1970s Capote, the bloated elf who made insulting remarks about celebrities on Merv Griffin and Johnny Carson, was far gone in alcoholism and drug abuse, and would die as a result—in 1984, at the sadly early age of 59.

It was around the time of his death that I fell in love with a very different Truman Capote—Truman Capote the writer.

Capote may not strike us as the likeliest person to create tales of unforgettable terror, but that is exactly how he made his first reputation, in the 1940s. His very first commercially-published tale, “Miriam,” written when he was still a teenager, is still one of his best: the lonely widow Miriam Miller, resident of New York City, is visited again and again by a little girl, oddly enough also named Miriam—a little girl whose visits come to seem increasingly threatening, though in ways Mrs. Miller can’t quite comprehend, as she undergoes a dizzying psychological disintegration. The tale is elegantly told, excruciatingly suspenseful, and features a final line which few readers ever forget.

The equally superb “Shut a Final Door,” which won the O. Henry Prize for Capote when he was all of nineteen, also features a haunted protagonist, in this case advertising executive Walter Ranney, who is harassed by constant anonymous phone calls from a voice “dull and sexless and remote,” which always answers Walter’s “Who is this?” the same way:

“Oh, you know me, Walter. You’ve known me a long time.”

As in “Miriam,” Capote is simply unparalleled in his description of his main character’s descent into—if not madness, then something much like it. And again, the story ends on a note that is genuinely disturbing and unforgettable.

His stories are not for those who like their fiction wrapped up neatly, all questions comprehensively answered. Capote was, in this early period, working very much in the Southern Gothic tradition of William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, and Eudora Welty. Stories like “A Tree of Night” and my personal favorite, “The Headless Hawk,” create an atmosphere of almost unbearable terror, but their resolutions are ambiguous and open to interpretation.

For an idea of just how good Capote was, consider the opening sentences from “A Tree of Night”:

“It was winter. A string of naked light bulbs, from which it seemed all warmth had been drained, illuminated the little depot’s cold, windy platform. Earlier in the evening it had rained, and now icicles hung along the station-house eaves like some crystal monster’s teeth. Except for a girl, young and rather tall, the platform was deserted.”

The picture Capote paints in words here is as vivid and precise in its way as an Edward Hopper painting. If you’re not feeling at least a little cold and desolate after those four sentences, then Truman Capote is not the writer for you.

The works I’m describing here, written between 1945 and 1948, were reprinted in book form in Capote’s A Tree of Night and Other Stories (1949), which is available in paperback today in an edition which also includes his lovely short (non-horror) novel The Grass Harp. Any horror aficionado should consider these stories required reading—not every one is horror, exactly, but except for a couple of lighter pieces, most make for very dark and disturbing reading (be sure not to miss either the sad, beautiful “Master Misery” or the sublime “Children on Their Birthdays,” another tale with a final line that hits somewhere in the back of one’s teeth.) The stories can also be found in the larger career-retrospective collection The Complete Stories of Truman Capote (2004).

Capote’s first novel proved to be his last foray into the Southern Gothic. A remarkably rich and painful book which features some of his most lyrical writing, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) represented the culmination of everything the author had learned about writing fiction from his early tales of terror. Its dreamlike narrative follows young Joel Knox on a journey to a crumbling mansion in the Deep South, where he has been led to believe that his father is waiting for him. His father is there, all right, but what’s really waiting for him is...something else. Other Voices, Other Rooms is partly a horror story and partly a coming-of-age tale, written in a tone which Capote later described, quite accurately, as having “a certain anguished, pleading intensity like the message of a shipwrecked sailor stuffed into a bottle and thrown into the sea.” It is, simply, a classic American novel.

With that, however, Capote moved on, writing lightweight fiction (Breakfast at Tiffany’s), holiday classics (“A Christmas Memory,” “The Thanksgiving Visitor”), and movies (Beat the Devil with Humphrey Bogart as well as a superb adaptation of The Turn of the Screw called The Innocents). In the 1960s he at last arrived at the “nonfiction novel” form in which he wrote what most critics consider his greatest work, In Cold Blood (1966)—which is certainly horrific, if not precisely “horror.”

Then, alas, the social butterfly Capote took over, hosting the most famous party of the 1960s (the now-legendary “Black and White Ball”) and slowly drinking himself into oblivion even as his fame increased exponentially throughout the 1970s. He managed to complete some short stories and nonfiction pieces (collected in 1980’s Music for Chameleons), but as a writer he was essentially finished. It was a sad end for a man who had burst on the scene three decades earlier with stories that are still among the finest examples of the very darkest of dark fiction.

--Christopher Conlon

(The Black Glove staff want to thank Christopher Conlon for this article)